2003 02: Dissertation Julie Spencer: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

=<font color=orange>during the months of August and September</font>= | =<font color=orange>during the months of August and September</font>= | ||

[More | [More [[All Mark Benecke Publications|articles from MB]]] [Articles [http://wiki2.benecke.com/index.php?title=Media#Interviews_.26_Articles <font color=lightgrey>about MB</font>]]<br> | ||

<html><a href="http://wiki2.benecke.com/images/7/73/Nocturnal_Oviposition_of_Blowflies_Julie_Spencer.pdf" target="_blank"><img src="http://wiki2.benecke.com/images/2/21/Nocturnal_Oviposition_of_Blowflies_Julie_Spencer_preview.jpg" border="0" height="150" align="middle"><figcaption>Click for PDF!</figcaption></a></html><br> | |||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

==<font color=orange>Abstract</font>== | ==<font color=orange>Abstract</font>== | ||

Blowflies are ubiquitous insects and have an ability to disperse, are small in size and have short generation times, therefore, it is hardly surprising that corpses are readily found colonised by insects and that as a corpse ages and the decomposition processes proceed, a different fauna will invade the body. With a change in attractiveness of the corpse through time, a succession of insect species will be encountered. These species will give some indication as to the history of the corpse, how old it is and what has happened to it. The postmortem interval (PMI) is one of the most important aspects of forensic entomology, since it aids in establishing a correct time frame in which the crime will have taken place. However, various factors may alter PMI, namely the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies, seeing as it can alter PMI by as much as 12 hours.<br> | Blowflies are ubiquitous insects and have an ability to disperse, are small in size and have short generation times, therefore, it is hardly surprising that corpses are readily found colonised by insects and that as a corpse ages and the decomposition processes proceed, a different fauna will invade the body. With a change in attractiveness of the corpse through time, a succession of insect species will be encountered. These species will give some indication as to the history of the corpse, how old it is and what has happened to it. The postmortem interval (PMI) is one of the most important aspects of forensic entomology, since it aids in establishing a correct time frame in which the crime will have taken place. However, various factors may alter PMI, namely the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies, seeing as it can alter PMI by as much as 12 hours.<br> | ||

Determination of the exact time of oviposition by blowflies had generally been made in the light of the conventional belief that blowflies are neither active nor do they lay eggs during the night. This method of estimating the time of oviposition was modified when Greenberg (1990:807) and Singh & Bharti (2001:124) both reported nocturnal oviposition by calliphorid species that are occasionally used as forensic indicators. The present research was concerned with investigating whether blowflies were active at night and laid their eggs during the months of August and September in South West Britain. It was found that nocturnal oviposition did not occur in any of the nine night trials undertaken.<br> | Determination of the exact time of oviposition by blowflies had generally been made in the light of the conventional belief that blowflies are neither active nor do they lay eggs during the night. This method of estimating the time of oviposition was modified when Greenberg (1990:807) and Singh & Bharti (2001:124) both reported nocturnal oviposition by calliphorid species that are occasionally used as forensic indicators. The present research was concerned with investigating whether blowflies were active at night and laid their eggs during the months of August and September in South West Britain. It was found that nocturnal oviposition did not occur in any of the nine night trials undertaken.<br> | ||

===<font color=orange> | ==<font color=orange>Chapter 1: Introduction</font>== | ||

===<font color=orange>Background to project</font>=== | |||

Forensic entomology is a discipline that has increased in importance over the past few decades. Today, the principal role of forensic entomology is to provide biological inferences regarding the circumstances surrounding, and the length of time, since human death, based upon examination of arthropods collected from or near corpses (Keh 1985:137; Catts & Goff 1992:253; Haskell et al. 1997:416; Benecke 2001:2). As early as 1979, Boyd recognised that entomologists could give a minimum time span on the time of death, i.e. the postmortem interval (PMI). In a death investigation, the time of death will focus the investigation into a correct time frame. Insects are attracted by specific states of decay, and particular species colonise a corpse for limited periods of time (Benecke 1998:799; Anderson 1999:856).<br> | |||

Consequently, there are two fundamental ways insects are used to estimate time of death. Firstly, blow fly developmental rates are used when the body is relatively fresh, i.e. in the first few hours, days or weeks after death. Secondly, faunal succession is analysed since different species of insects infest the body at different times (Boyd 1979:4; Haskell et al. 1997:416; Benecke 1998:798; Anderson & Cervenka 2002:174). Sarcosaprophagous flies, i.e. those which feed on dead animal material, particularly calliphorids, are recognised as the first wave of the faunal succession on human cadavers (Nuorteva 1977:1080; Smith 1986). They are, therefore, the primary and most accurate forensic indicators of time since death (Grassberger & Reiter 2002:177).<br> | |||

In general, the blowflies are the first insects to colonise remains, although the species will vary with geographical region and season (VanLaerhoven & Anderson 1999:32; Carvalho & Linhares 2001:604). They are constantly in search of fresh carrion to lay their eggs on and this explains their early presence on corpses. Eggs are usually laid in large batches, up to 250 eggs at a time. Blowflies will lay their eggs in almost any orifice and it has been estimated that as many as 40,000 eggs may be laid on any adult body (Greenberg 1991:566; Sharp 1996:9). If one female has laid her eggs, many others become attracted to the same area and lay their eggs at the same site, therefore, the egg mass may be several square centimetres in size (Barton Browne et al. 1969:1003; Anderson 2001:144; Anderson & Cervenka 2002:174). Oviposition in blowflies is elicited primarily by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds as well as moisture, pheromones and tactile stimuli (Ashworth & Wall 1994:303).<br> | |||

Blowflies are diurnal species and are considered to be inactive at night. Therefore, eggs are generally not laid at night, and a body deposited at night may not attract flies until the following day (Anderson 1999:856; Anderson 2001:145). At present, the research into the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies has been limited. Greenberg (1990:807) and Singh and Bharti (2001:124) maintain that calliphorid flies can lay eggs during the night. However, research carried out by Tessmer et al. (1995:439) concluded that egg deposition does not occur in the nocturnal hours.<br> | |||

In a given situation a forensic archaeologist has the capacity to provide guidance and advice on other fields of expertise by having a basic understanding of a broad range of forensic sciences from pathology and forensic anthropology, to forensic entomology and environmental archaeology. For example, a forensic archaeologist may be asked to collect samples in the absence of an entomologist. Therefore, it is imperative that a forensic archaeologist keeps up to speed on the progress being made in various fields, especially the up and coming field of forensic entomology. By understanding the following study, forensic archaeologists will allow themselves to become more judgemental with regards to estimates in postmortem interval (PMI) and this is, without doubt, one of the most fundamental elements in a forensic investigation.<br> | |||

===<font color=orange>Factors influencing the oviposition of blowflies</font>=== | |||

Blowflies are ubiquitous insects that impact on man and animals in many ways. There are positive and negative aspects associated with these invertebrates. They transmit a variety of human diseases and can cause economic loss due to myiasis or fly strike. For the most part they are considered highly detrimental. Nonetheless, they can also be regarded as beneficial insects. For example in maggot therapy and as pollinators of agricultural crops in controlled areas. However, knowledge of blowflies can also be employed in a unique setting. Their ability to rapidly locate a body enables them to colonise human and animal remains that have been wrapped, buried or otherwise protected. The omnipresent nature of insects makes their eventual appearance at a death scene a near certainty. In consequence, their life cycles and developmental rates can aid in determining the time of death in criminal cases (Nuorteva 1977:1072; Avancini & Linhares 1988:73; Turner 1991:132; Anderson 2000:824).<br> | |||

Cadavers undergo a series of predictable changes during decomposition, and are ëvisitedí by a succession of flies and other insects (Goff 1992:748). This ordered process has handed us an invaluable tool for estimating the age of cadavers, and the biology of this process has resulted in the science of forensic entomology (Dadour et al. 2001:48). Fly developmental rates underpin the accuracy of the PMI. | |||

Calliphora vicina (Robineau-Desvoidy), commonly known as the blue bottle, is the most frequent species of blowfly found on human corpses in the UK (Smith 1986; Pounder 1991:469). Adult C. vicina are large and conspicuous due to their slow, powerful buzzing flight.<br> | |||

They are extremely abundant in open and urban surroundings as well as in association with humans and their environments. The species has an almost global distribution, being found throughout the Holarctic region as well as South America, North India, Australia and New Zealand (Smith 1986). In the climatic context of northern Europe, certain species, particularly Calliphora vicina, are of special forensic interest because of their ability to develop to pre-adult stages at 3-4ƒC, and the fact that adult populations occur over very long seasonal spans including cool months. They exist in most habitats from sea level to high ground, and both urban and rural habitats (Davies & Ratcliffe 1994:245).<br> | |||

Blowflies, such as Calliphora, owe their forensic importance to their ability to locate human remains within seconds of death and to oviposit within an hour in favourable conditions (Pounder 1991:469; VanLaerhoven & Anderson 1996; Haskell et al. 1997). Nuorteva (1977:1080) maintains that an intact dead body does not immediately attract sacrosaprophagous flies for oviposition. In the presence of vomitus, blood or an open wound, however, oviposition may be established in a few minutes. In fact, open wounds may induce oviposition in the still-living body. Oviposition of blowflies on woundless corpses starts in general the second day after death, but it may also occur earlier when flies are abundant in the environment and the dead body is lying in sunshine (Nuorteva 1977:1081).<br> | |||

There are numerous species of sarcosaprophagous flies that are confined to environments of a quite specific type (e.g. forests, shores, hill tops, cities), and these flies may by their eggs verify the transport of a corpse through their domain. Only a few species, however, possess eggs characteristic enough to be identified directly. In considering forensic evidence based on fly eggs, it is necessary to remember that fly eggs are easily destroyed by unfavourable environmental conditions, especially by heat and dessication (Davies 1948:71; Nuorteva 1977:1080).<br> | |||

The oviposition behaviour of insects is usually complex (Barton Browne 1960:16). The attraction of blowflies to their hosts involves a broad range of behaviours including initial activation, orientation and landing behaviour culminating in oviposition. Each stage requires a combination of visual and olfactory cues with tactile cues possibly acting in the final stages (Ashworth & Wall 1994:303). Oviposition in sandflies is also controlled through a combination of complex interactions between environmental, physical and chemical factors (Nieves et al. 1997:733). Oviposition is elicited primarily by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds, as well as moisture, pheromones and tactile stimuli (Ashworth & Wall 1994:304). However, some species of blowfly are dependent on their gonadotrophic development stage in order to be attracted to carrion baits (Crystall 1983:220).<br> | |||

A sequence of activation, orientation and then landing is observed in host location (Hall 1995:335; Ashworth & Wall 1994:303; Sutcliffe 1987:611). Pre-landing and landing stimuli are the most important in attracting flies to the host. However, the responses to exogenous stimuli are modulated by endogenous factors, such as the nutritional and physiological state and the sex of the fly. Following landing on the host, it is probable that tactile, thermal and chemical stimuli are also involved in the selection of oviposition sites during an initial ësearchingí phase (Cragg 1956:467; Barton Browne & Rogoff 1959:189; Holt et al. 1979).<br> | |||

====<font color=orange>Temperature</font>==== | |||

Fly activity is inhibited not only by darkness but also by cold weather and rain. The only exceptions to this are the flies of the family Sarcophagidae, which fly in the rain. In the sub-arctic and boreal regions, temperatures below 12ƒC inhibit the flying activity of the cold-acclimatised flies. The activity is also inhibited by highly elevated environmental temperatures, which may interrupt the oviposition of flies in the hottest hours of the day (Nuorteva 1977:1082). | |||

The ovipositional behaviour of flies may likewise be affected by microclimatologic conditions. Considerable differences in the composition of fly faunas occur in shady areas and in sunshine. The differences are, however, of a quantitative rather than a qualitative nature. According to Cragg (1956), the blowfly Lucilia sericata does not usually oviposit on carcasses with a surface temperature below 30ƒC. In temperate climates only carcasses warmed by sunshine reach such high temperatures. Therefore, if eggs of this species are found on a human corpse lying in a place that is in shadow during the entire day, the finding may be interpreted as indicating that the corpse has been removed from an area in which there was sunshine earlier (Shean et al. 1993:938).<br> | |||

It has been said that blowflies will only oviposit when media reach certain optimum temperatures, yet Payne (1965:592) observed that frozen pigs attracted sacrophagids within five minutes of being taken from the freezer. Eggs of calliphorids were deposited ëwhile the carcasses were still partially frozen. Some carcasses required as much as 6 hours to thawí (Keh 1985:141). According to Nuorteva (1977:1080), the temperature of the body must reach a required threshold before Lucilia sericata will oviposit.<br> | |||

Mann et al. (1990:105) state that flies will continue to visit a carcass and lay eggs in cold weather down to about 5 to 13†C. Below 0†C, the flies will die. Maggots will also die if they are exposed to cold temperatures. However, those maggots that have already entered the body cavities, for example, the head, chest, abdomen and vagina will be able to develop in freezing weather since they create their own heat.<br> | |||

In an experiment performed by Fitzgerald (1996:62), oviposition continued to be noted throughout November and December 1998, despite regular night time temperatures falling below 0ƒC. The baits used were subjected to an overnight minimum of ñ2.40C between the 5th and 6th December, but despite this chilling infestation of the bait, oviposition was noted within 10 days. The lowest temperature at which oviposition was observed was 9.10C, whilst the bulk of ovipositional activity noted during November and December 1998 appeared to have occurred during the afternoons when the west facing window of the experimental building admitted afternoon sunlight and temperatures became elevated (Fitzgerald 1996: 62). This experiment was also carried out in the southwest of Britain.<br> | |||

====<font color=orange>Semiochemicals</font>==== | |||

The behavioural response of blowflies to semiochemicals appears to be of particular importance regarding oviposition. Ashworth and Wall (1994:305) summarised findings of experiments already performed relating to the olfactory responses of Lucilia sericata to semiochemicals. They concluded that host location and oviposition involves at least two distinct sets of semiochemical cues. Attraction to carrion is brought about by sulphurous decomposition whereas oviposition is elicited by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds. As early as 1958, Barton Browne (1958:241) discovered that eggs themselves, or a chemical ëfactorí produced during their laying might stimulate females to oviposit. Without doubt, oviposition is elicited by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds, nonetheless, other factors such as moisture, temperature or pheromones will also be influential in regulating the response of the blowfly to oviposit.<br> | |||

Wall and Fisher (2001:212) emphasise that the presence of semiochemicals will increase the probability of an insect detecting and arriving at an oviposition site. However, for many Diptera, visual cues may become increasingly important in directing landing and searching behaviour at close range to the site. For example, bot flies, appear to use semiochemical cues to locate their hosts, but it is some component of the eyes or nostrils that provides the oviposition cue (Rakusin 1970:1155; Anderson & Nilssen 1996:338). | |||

====<font color=orange>Moisture</font>==== | |||

Moisture has also been shown to be an important stimulant for oviposition in blowflies (Barton Browne 1962:383; Ashworth & Wall 1994:304). Barton Browne (1962:389) concluded that the females of L. cuprina would not oviposit freely unless they had made tarsal contact with free moisture beforehand. He concluded that oviposition in situations where free moisture was present would tend to minimise the risk of death through water loss. His own field observations noted that L. cuprina did not select dry situations on either sheep or carrion for oviposition.<br> | |||

====<font color=orange>Pheromones</font>==== | |||

Barton Browne et al. (1969:1003) observed that formations of aggregations of ovipositing females was due, in part, to the preference shown by gravid females for oviposition sites already occupied by ovipositing females. They discovered that females of L. cuprina are stimulated to lay by the presence of other flies and that the stimulation must be chemical in nature. Norris (1964:280) described an experiment with the locust Schistocerca gregaria that demonstrated the existence of an oviposition pheromone. The role of this pheromone in the gregarious oviposition behaviour of the locust is similar in a number of ways to that in L. cuprina. In both the contact chemical sense is more important than the olfactory one in determining spatial distribution of egg laying. El Naiem and Ward (1990:456; 1991:87) discovered the existence of an oviposition pheromone associated with the eggs of L. longipalpis. This pheromone has been isolated from female accessory glands and is secreted on to the eggs during oviposition (Dougherty et al. 1992:1165).<br> | |||

Female blowflies are often attracted to the same sites to lay their eggs. The ensuing oviposition frenzy often results in a mound containing thousands of eggs of several species (Greenberg 1991:567). Consequently, studies have recorded these observations in the field. Firstly, Barton Browne (1958:246) observed that while the first eggs laid are the result of the attraction of gravid females to the host, the laying of later ones is in part due to the presence of already ovipositing flies. Secondly, Holt et al. (1979:250) reported the attractiveness of stationary, ovipositing females of Co. hominivorax to other females engaged in searching for an oviposition site.<br> | |||

Finally, Fenton et al. (1999:147) performed an experiment that concerned the effects of oviposition aggregation on the incidence of sheep blowfly strike. They discovered that the presence of existing strikes on an individual sheep might be important in attracting further oviposition and larval survival. Pre-struck sheep are thought to be highly attractive to gravid females so that once a strike has become established, successive females will be attracted to, and oviposit around the area of strike, thereby prolonging the lifetime of the strike (Eisemann 1988:275).<br> | |||

====<font color=orange> | ====<font color=orange>Role of olfaction</font>==== | ||

Barton Browne (1960:16) discovered that in the presence of sufficient odour concentrations, the contact stimuli of the blowfly plays little or no part, therefore, olfactory stimuli incite the flies to oviposit. This point was reiterated a few decades later since, studies carried out throughout the late 1980s and the early 1990s discovered that odour cues were more important than visual cues in attracting flies (Eisemann 1988:273; Hall et al. 1995:77; Wall & Warnes 1994:239). | |||

The odours of tissue putrefaction are highly attractive to gravid females of primary facultative species, such as L. cuprina and L. sericata, which will both feed and oviposit at sources of these odours. However, they are less attractive to gravid females of obigate species, such as C. hominivorax, which feed but will not naturally oviposit at sites of putrefaction such as carrion (Hall 1995:343).<br> | |||

The faint odours from a fresh corpse are carried downwind. Thus, some of the first flies on the scene are strongly flying species, which track upwind following the odour plume; for example the bluebottles, Calliphora vicina or Calliphora vomitoria. These are the two commonest species involved with forensic cases in Europe. Evidence suggests that C.vicina will readily oviposit in response to olfactory cues alone and physical contact with carrion is not a pre-requisite. Infestation of the carrion is then possible through the migration of the larvae from the site of oviposition (Ashworth & Wall 1994:305; Wall & Fisher 2001:213).<br> | |||

Adult blowflies are attracted in large numbers by the odours of decay, often within a few hours of death. Wounds or open sores and ulcers on living humans may also attract blowflies before death. In such cases, the larvae feeding on living persons or animals cause a disease condition known as myiasis. The attractive odours are mainly due to bacterial action on dead tissues and include hydrogen sulphide, ammonia and organic sulphur containing compounds, including methyl mercaptan, dimethyl disulphide and dimethyl trisulphide (Gill 1982: 227). Odour location is very precise in blowflies, enabling them to locate bodies even in hidden locations, e.g. through air vents in the walls of buildings (Hall 1995: 467).<br> | |||

Rodriguez & Bass (1985:850) emphasise that odours given off by a decomposing cadaver in a shallow burial site appear to be easily detected by various carrion insects. It is well established that insects have highly developed olfactory systems that are capable of detecting odours or chemical substances that may only be present in microscopic quantities.<br> | |||

====<font color=orange>Nocturnal oviposition</font>==== | |||

A common assumption of forensic entomologists in estimating a PMI is that blowflies, the primary and initial arthropod colonizers of carrion, are not active at night, and therefore, no oviposition occurs between sunset and sunrise. Nuorteva (1977) states that sarcosaprophagous flies (i.e. Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae and Muscidae) fly only during the daytime.<br> | |||

As with most animal species, there are few absolutes in blowfly behaviour. Blowflies are diurnal species and usually rest at night. Therefore, eggs are not usually laid at night, and a body laid at night may not attract flies until the following day (Anderson 2001:145). The research that has been completed concerning the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies is relatively limited. In 1951, Green (1951:475) carried out a study relating to blowfly activity in slaughterhouses. He discovered that blowflies oviposited in large numbers when there was a high prevalence of sunlight. However, the flies also oviposited on meat in dimly lit sheds. Field observations at night were limited to three periods of 1-2 hours and the population examined consisted of 95% Lucilia and 5% Calliphora. Green (1951:484) observed that Calliphora flew and oviposited during the night, however, Lucilia seldom did. In laboratory conditions, both genera oviposited in total darkness. These observations by Green (ibid.) were recorded in conjunction with another primary objective therefore the data is not conclusive.<br> | |||

It was not until forty years later that Greenberg (1990:807) published data pertaining to the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies. Greenberg performed a study on the south side of Chicago and found that Phaenicia sericata oviposited in small numbers on rat carcasses exposed nocturnally near sodium vapour lamps. Over the two-year trial period, ovipositions occurred in approximately 33% of the trials. Greenberg (ibid.808) emphasises that a forensic entomologist should be aware of the possibility of nocturnal oviposition in the calculation of PMI. There could be as much as a 12-hour difference in the estimate of PMI since the determination of PMI is based on the oldest specimens and these could result from nocturnal oviposition. For example, oviposition might actually have occurred at 21h00 the previous night instead of 09h00 the next day.<br> | |||

Singh and Bharti (2001:124) recognised a flaw in Greenbergís (1990:807) experiment and in consequence modified it in order to examine whether flies will oviposit at night. Instead of the bait being placed on the ground near bushes, the bait was in a petri dish that was placed on a wooden platform fixed on the top of a pole 6 feet in height. The evaluation period was from 22h00-03h00. The experiment substantiated the report that calliphorid flies can lay eggs during the night. However, the number of eggs laid was greatly reduced in comparison to the daytime. Ovipositions occurred in 33% of cases, this matches Greenbergís (1990:807) results.<br> | |||

The three aforementioned studies demonstrate that nocturnal oviposition can occur in blowflies. However, alternative research into nocturnal oviposition suggests that the results are not conclusive. Nuorteva (1977:1081) states that it is important to note that sarcosaprophagous flies of the families Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, and Muscidae, i.e. the flies that invade corpses first, fly only during the daytime, see Figure 1. Therefore, if fly eggs are detected in a corpse during the night or early morning, the conclusion can be reached that death occurred during the previous day or earlier.<br> | |||

[[File:Julie spencer fig 1.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Figure 1: Diurnal activity of blowflies. Taken from: Nuorteva, P. (1977:1081)]] For instance, Tessmer et al. (1995:439) reported that blowflies failed to lay eggs at night both in urban habitats with lighting and rural habitats without lighting. The study included three evaluation periods: 13h00-20h00, 21h00-05h00 and 06h00-13h00. The researchers observed that egg deposition did occur prior to and following the nocturnal evaluation period and no egg deposition occurred on any carcass during the nocturnal hours regardless of the artificial lighting. See Appendix A for a summary of the published experiments carried out concerning nocturnal oviposition.<br> | |||

Anderson (1999:856) was involved in a case in Manitoba, Canada, where bear cubs were disembowelled and shot at night at a rubbish dump in the vicinity of large numbers of blowflies. However, the carcasses were not colonised until the following morning, i.e. nocturnal oviposition did not occur. Haskell et al. (1997:421) performed a two-year research project in rural northwestern Indiana and failed to detect nocturnal oviposition.<br> | |||

In conclusion, there are two opposing sides in the research involving the nocturnal behaviour of blowflies, and there are no published studies in Britain.<br> | |||

===<font color=orange> | ===<font color=orange>Aims and Objectives</font>=== | ||

The aim of this research is to determine the hither to unknown nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies in southwest Britain during the months of August and September. The question that needs to be answered is: are blowflies active during the period from sunset to sunrise? It is an area that needs to be investigated since cessation of oviposition at night is of forensic importance because it could change an estimate of PMI by as much as 12 hours (Greenberg 1990:807).<br> | |||

The objectives of this project are to:<br> | |||

* Monitor the oviposition behaviour of blowflies during three daytime evaluation periods as a control mechanism<br> | |||

* To observe and record the nocturnal oviposition behaviour<br> | |||

* Record temperature and relative humidity at the site of the experiment<br> | |||

* Rear the eggs in order for identification of species to be simplified when oviposition has occurs<br> | |||

* Evaluate the importance of nocturnal oviposition on estimating time since death.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Chapter 2: Methods</font>== | |||

The methods used during the course of this investigation were devised by the author in concurrence with previous research and conducted in the authorís back garden in Bournemouth.<br> | |||

===<font color=orange>Experimental Procedure</font>=== | |||

Frozen pieces of pigís liver were obtained from a butcherís and kept frozen until the morning of the experiment. On the day of the experiment the liver was thawed and kept refrigerated at 4ƒC until it was needed at 20.00 hrs for the first evaluation period. Grisbaum et al. (1995:165) demonstrated that refrigeration did not inhibit oviposition by necrophilous flies.<br> | |||

The site of the experiment was in the authorís back garden in Winton, Bournemouth. This is an area in Southwest England. There are no streetlights or other sources of illumination that project on to the garden, i.e. no artificial lighting. | |||

Two different samples were used. One piece of liver, roughly 100g in weight, was placed in a sterilised dish and placed upon a wooden platform which was fixed on the top of a wooden pole that measured 60cm in height. The second piece of liver, roughly 100g in weight, was placed in a sterilised dish that was placed on the ground. A mesh surrounded both bait samples so as to deter scavengers such as foxes and cats that live in the neighbourhood. The mesh squares measured 6mm by 4mm.<br> | |||

The evaluation periods throughout the night were comprised of 2-hour slots. Therefore they ran from 20.00-22.00 hrs, 22.00-0.00 hrs, 0.00-02.00 hrs, 02.00-04.00 hrs and 04.00-06.00 hrs respectively. The liver was changed every two hours.<br> | |||

The experiments were performed during the months of August and September in three 3-day blocks, from 11th-13th August, 18th-20th August and 8th-10th September.<br> | |||

After exposure, each bait sample was placed in Ziploc bags along with wood shavings so that potential excess fluid could be absorbed and the opening was sealed. Minute perforations were made using a pin to allow air to enter the bag and so that carbon dioxide build up would be avoided. The same Ziploc bags were then stored in the garden shed and the ambient temperature was recorded. The temperature recorded in the garden shed measured 22-24ƒC throughout the time of the experiment. The bags were observed for several weeks in order to detect the presence of fly maggots.<br> | |||

Since no maggots developed and in consequence no flies emerged it meant that no identification was necessary by a specialised entomologist since oviposition had not occurred.<br> | |||

===<font color=orange> | ===<font color=orange>Control Experiment</font>=== | ||

A control experiment was undertaken on the morning of the first experiment, i.e. 11th August. Liver was placed on the ground and on the elevated platform during a daytime period of 10h00 until 13h00. Another control experiment was performed on the first day of the second block of experiments, i.e. 18th August. The evaluation period was from 10h00 until 13h00. Finally, a control experiment was carried out on the first day of the third block of experiments, i.e. 8th September. The evaluation period was from 10h00 until 13h00.<br> | |||

All three of these control experiments were performed in order to ascertain whether blowflies were still active during the daytime in southwest Britain and whether they would still be ovipositing at this time of year.<br> | |||

===<font color=orange>Temperature Recording</font>=== | |||

At the beginning of each 2-hour evaluation period, the temperature was measured at the site of the experiment by a digital thermometer, a Thermo-Hygro. Relative humidity was also measured every two hours by the same equipment. All measurements were made 40cm from the bait.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Chapter 3: Results</font>== | |||

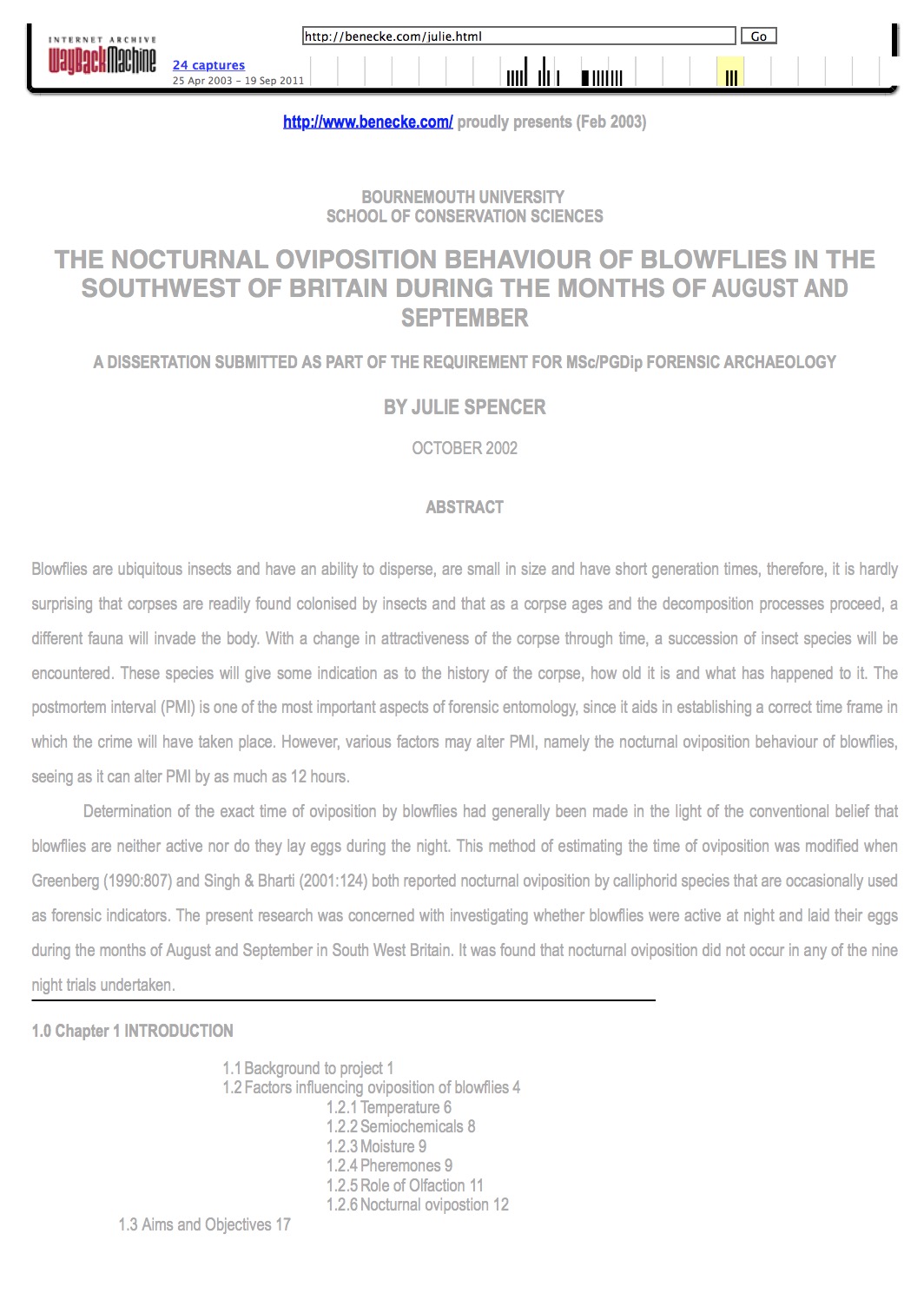

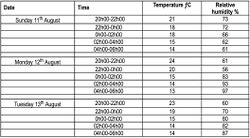

[[File:Julie spencer table 1.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 1: Oviposition behaviour of blowflies in SW Britain, Trial 1]] Table 1 presents the results of the first block of experiments carried out in August. The evaluation periods are depicted for each night. The results are shown for one daytime period and for each night, both for the ground experiment and the elevated experiment.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

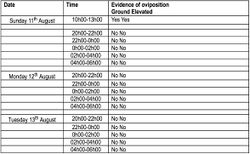

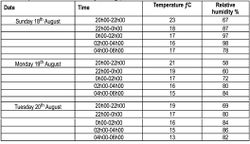

[[File:Julie spencer table 2.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 2: Oviposition behaviour of blowflies in SW Britain, Trial 2]] Table 2 presents the results of the second block of experiments carried out in August. The evaluation periods are depicted for each night. The results are shown for one daytime period and for each night, both for the ground experiment and the elevated experiment.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

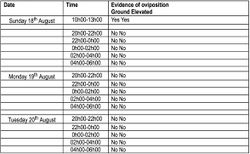

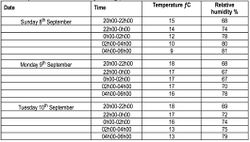

[[File:Julie spencer table 3.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 3: Oviposition behaviour of blowflies in SW Britain, Trial 3]] Table 3 presents the results of the final block of experiments carried out in September. The evaluation periods are depicted for each night. The results are shown for one daytime period and for each night, both for the ground experiment and the elevated experiment.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

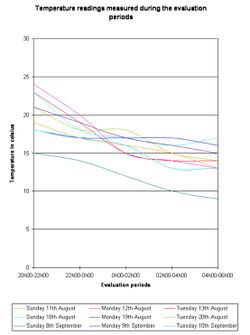

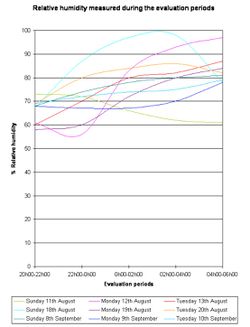

[[File:Julie spencer fig 2.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Figure 2: Temperature readings measured during the 9 night trials]] [[File:Julie spencer fig 3.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Figure 3: Relative humidity readings measured during the 9 night trials]] Figures 2 and 3 (on the left) illustrate the temperature in Celsius and % relative humidity readings taken at the beginning of each evaluation period for each of the nine nights.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Chapter 4: Discussion</font>== | |||

Previous research into the field of nocturnal oviposition of blowflies has yielded quite varying results. On the one hand, some studies demonstrated that blowflies do oviposit during the period form sunset to sunrise and, on the other hand, other studies have failed to record oviposition. The current study falls into the latter group since no oviposition occurred during the 9 night trials. This experiment substantiates the report that calliphorid flies do not lay eggs during the night (Tessmer et al. 1995:444).<br> | |||

The experiment was set up so that it incorporated the parameters set out in Greenberg and Singh & Bhartiís experiments (Greenberg 1990:807; Singh & Bharti 2001:124). Singh & Bharti (2001:125) proposed that there was a flaw in Greenbergís experiment due to the fact that he laid the bait on the ground and that the potential for flies just to crawl to the bait was facilitated. In contrast, their experiment placed the bait on a raised platform so that it could be ascertained whether flies were still active during the period from sunset to sunrise, i.e. by flying to the bait. The current experiment incorporated both the ground bait, as well as the bait being placed on an elevated platform so that no discrepancies could arise. Even then, no oviposition occurred either on the ground bait or on the raised bait. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is no real differentiation necessary between an elevated and a ground bait. If the flies are active in an area at night, they will surely locate the bait or corpse no matter what.<br> | |||

Lighting in the surrounding area might play a crucial role as to whether blowflies will oviposit at night. In the current study, no artificial lighting was present within a 30 metre radius of the bait placement. The walls of the back garden were also relatively built up so no outside light could get in from surrounding houses. Greenbergís bait was in the vicinity of sodium vapour lamps, subsequently they could have influenced the behaviour of the blowfly and in consequence aided in the nocturnal oviposition. However, Singh & Bharti noticed that flies still laid their eggs even in the absence of artificial lighting. Nevertheless, the current study undertaken in Bournemouth and a study completed in Southern Louisiana (Tessmer et al. 1995:439), demonstrate that in the absence of artificial lighting no oviposition by calliphorids will occur. A further area of research that needs to be conducted involves credible field data pertaining to fly activity at levels of varying light intensities. With an increase in the amount of security lighting and street lamps, these factors could play some sort of role in fly behaviour. For example, Anderson (2001:151) noted that when flies were kept in constant darkness in a laboratory and then the light was switched on, this instigated the flies to commence laying their eggs. Light is, without doubt, a fundamental factor influencing blowfly behaviour.<br> | |||

As with any study carried out, the time of year will be critical in determining the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies. Certain species of fly will be more dominant at certain times of year in particular climates and habitats. For example, if one considers the studies already conducted, the locations of the experiments are very unrelated, i.e. Southern Louisiana, U.S.A, Chicago, U.S.A and Patiala City, India. The latter both saw evidence of nocturnal oviposition, however, the species of blowfly recorded differed apart from the common blowfly Calliphora vicina that was present at both sites. There is no way yet to establish a pattern of behaviour of blowflies in specific geographical locations because not enough research has been performed, therefore, it is hard to define trends or certainties. Greenberg (1990:807) and Tessmer et al. (1995:439) both performed their studies during the months of July and August, whereas Singh & Bharti (2001:124) experiment was conducted during the months of March and September. Since none of these exact days or months have been duplicated identically in an experiment, it is hard to determine whether the time of year will alter the results significantly as far as nocturnal oviposition behaviour is concerned. The current experiment was conducted throughout August and September in the UK, the later summer months. Perhaps if the experiment had been carried out in the spring or early summer months, the results might have been different.<br> | |||

The size and species of the bait employed in the experiment may have influenced the behaviour of the blowflies. Hanski (1987:257) highlights the fact that there is an apparently random element in the insect infestation of carrion and this perhaps reflects the local variation in the environment. Blackith & Blackith (1990:700) and Kuusela & Hanski (1982:337) all posed the question of whether carrion flies prefer certain types of corpse, for example; birds, rabbits, quail or mice, and concluded that they show no real preference. However, this assumption is perilous since there are variations shown by fly populations as a whole. Various researchers have observed that blow flies respond differently to butchered meat as compared to natural carrion and they also concluded that the size of the carrion and the species of animal used will also affect the behaviour of the blow flies (Norris 1965:47; Smith & Wall 1997:42). For example, Greenberg & Tantawi (1993:483) noticed that in field experiments P. terraenovae and C. vomitoria prefer larger carcasses as breeding material, Erzinclioglu (1986:9) noted that C. vomitoria does not oviposit on mice and Nuorteva (1977:1081) maintained that P. terraenovae is particularly attracted to human cadavers. The size of the bait in the present study might have been too small and in consequence not attracted the flies to land and oviposit and perhaps the nutritional value of pigís liver does not attract the blowfly. Nonetheless, it must be noted that the blowflies did lay eggs during the day on the liver.<br> | |||

Throughout the existing research, the length of time the bait was placed on the platform or on the ground might have predisposed the oviposition behaviour of the blowflies. Since the liver was changed at the beginning of every two hour evaluation period, perhaps there was not enough time for the sulphur rich volatiles associated with the breakdown products of tissues to be released. Hall (1995:341) maintains that odour cues are more important than visual cues in attracting blowflies to a specific site and Ashworth & Wall (1994:305) proved that initial attraction to carrion is brought about by sulphurous decomposition. They carried out an experiment in a wind tunnel and found that gravid females of the species L.sericata have been shown to increase both the number and duration of their flights in response to liver odours. This suggests an increased level of searching behaviour as a result of odour cues. Since the pigís liver was kept refrigerated at 4ƒC throughout the day, before the experiment began at 20h00, there is the possibility that the decomposition process of the liver had not yet commenced, therefore retarding the release of sulphurous elements. In consequence, the blowflies would not have been attracted to the liver.<br> | |||

Temperature is another parameter that could prejudice the behaviour of the blowflies at night. Blowflies are still able to function at quite low temperatures, for example, Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy), is the most cold tolerant of all calliphorid species (Grassberger & Reiter 2002:177). Calliphora vicina is also highly tolerant to the cold and can develop at temperatures of 3-4ƒC (Davies & Ratcliffe 1994:245). Fitzgerald (1996:62) discovered that the lowest temperature that oviposition was observed at was 9.1ƒC. In the present study, the temperature during the evaluation periods at night did not fall beneath 9ƒC. There was only one night, Sunday 8th September between 04h00 and 06h00 when the reading was 9ƒC, as can be seen from Figure 5 in the results section. Therefore, it can be concluded that temperature was not a key element in determining the nature of blowfly behaviour during the nocturnal hours. | |||

Another factor to consider is that blow flies have a preference for laying their eggs in the cracks and crevices of the human body, i.e. the nose, ears and mouth, therefore the bait used in the current study will not have replicated the human corpse. A pigís liver is a piece of meat that does not contain obvious orifices. Greenberg (1990:808) utilised rats and Tessmer et al. (1995: 440) employed chickens in their respective studies. As with all of the aforementioned parameters, individually they may not be the single causative agent as to why the blowflies did not oviposit at night, but collectively they may contribute to the inactivity of the blowflies.<br> | |||

Since the research undertaken provides negative results as far as nocturnal oviposition is concerned, this could have far reaching consequences, for example, in a court of law. There are certain researchers who believe that nocturnal oviposition occurs and there are those who are opposed to the idea. In Hungary, a ferry skipper was condemned to life imprisonment because he was accused of murder. He had arrived at work at 6pm and discovered the body of a postmaster a few hours later. At the trial no attention was paid to the newly hatched larvae, measuring 1-2mm in length, that was retrieved from the body during the postmortem. The case was reopened 8 years later. At the new trial, a forensic entomologist stated that no flies were active in Hungary at and after 6pm during the month of September. L.sericata hatches after 10-11 hours and P.terraenovae after 14-16 hours at 26ƒC, therefore , it was not possible that the eggs could have hatched if they had been laid during the day of the postmortem. They must have been laid the previous day before 6pm. Following this evidence the skipper was released (Nuorteva 1977:1081). If nocturnal oviposition is believed to occur, the ferry skipper could have been convicted of murder. This is one example where it is fortunate that the forensic entomologist believed that nocturnal oviposition does not occur or else the skipper would have been convicted. A certain amount of controversy might be created with researchers utilising the assumption that flies do oviposit at night. For example, in a court case, there is the potential that an individual may be unlawfully convicted or a guilty man may go free. It is only with more concrete evidence pertaining to the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of flies, will this supposition become more acceptable in court.<br> | |||

However, everything is dependent on development rates of blowflies and oviposition behaviour of flies in specific geographical locations. Temperature will also play a role as well as altitude and latitude in the behaviour of blowflies. It would be advantageous to conduct research in this field but on a far broader scale, throughout various different geographic regions so that more substantial information is available.<br> | |||

Cox (1998:21) highlights the fact that a forensic archaeologist will have a broad based knowledge of the forensic sciences; from entomology right the way through to anthropology. Archaeological evidence gained from excavating a victim the day after the murder or even a thousand years later can be crucial in forensic investigations. Other relevant buried factors and evidence may lie in association with the victim, including the specialised field of entomology. Insects are ideal to use in forensic cases since they are sufficiently robust to be preserved, they each have a preferred niche, they all have relatively understood parameters and they are highly sensitive, for example to temperature. Arthropods are even more valuable when used in juxtaposition with other environmental indicators such as pollen, soil and plant remain analysis.<br> | |||

Forensic archaeologists need to be aware of the field of entomology since flies will oviposit on a corpse, be it a surface scattering of remains or buried human remains. There is the need to be aware of the preponderance for fly activity in and around a corpse. For instance, when confronted with a maggot-infested body whose skeletal remains are present in a grave, the forensic archaeologist should be able to collect the relevant soil samples as well as entomological and toxicological samples in the absence of an entomologist. Nocturnal oviposition behaviour is an area that is rather crucial seeing as an estimate of PMI could be altered as much as 12 hours. Consequently, it is imperative that investigators know that if fly eggs are detected in a corpse during the night or early morning, the conclusion can then be reached that death occurred during the previous day or earlier (Nuorteva 1977; Anderson 1999). Forensic archaeologists need to be aware of other specialists and their associated techniques so that their knowledge can be ëtaken on boardí and utilised at the appropriate time in forensic investigations.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Chapter 5: Conclusion & Recommendations for further research</font>== | |||

The present research can be viewed as a pilot study for a more comprehensive investigation of nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies in Britain. This could be achieved by field trials using carcasses of body mass comparable to that of humans. Pigs have been used by many researchers as experimental subjects.<br> | |||

At present there is not enough substantial information, i.e. published data, pertaining to the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies. It is therefore of relevance to investigate, under field conditions, the response of forensically important Diptera to various baits during the period from sunset to sunrise. Where possible, it would be advantageous to replicate the situations encountered at various forensic crime scenes more closely, in order to provide more accurate information regarding this subject. Nonetheless, no matter how defined the experiments prove to be, the varying artificial environments created in the various experiments will only allow for the formulation of provisional conclusions.<br> | |||

* One avenue to pursue involves the creation of a set of credible results relating to fly activity at levels of varying light intensities.<br> | |||

* A second parameter that needs to be monitored involves specific minimum and maximum temperatures that sarcosaprophagous insects will oviposit at.<br> | |||

* Another area that needs to be investigated concerns circadian rhythms and whether they play a role in influencing the blow flies nocturnal oviposition behaviour. Is it fair to say that the results obtained from this pilot study demonstrate that blowflies truly are a diurnal species governed by their circadian clocks? They are, after all, inactive during the night.<br> | |||

* Finally, since there is the possibility that blow fly species have different oviposition preferences, perhaps due to the fact that different carcasses will have different nutritional value, this could be investigated in further studies.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Acknowledgements</font>== | |||

I would like to thank the following individuals, particularly, Dr Helen Smith of Bournemouth University for encouragement and support during the planning, research and preparation of this dissertation, and I would also like to thank Dr Mary Lewis of Bournemouth University for all the invaluable input she gave in the latter stages of the dissertation. My thanks also goes to Dr Mark Benecke of International Forensic Research Consulting for his innumerable suggestions and assistance over the course of the last few months and to Dr Martin Hall of the Natural History Museum for answering all kinds my queries.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>References</font>== | |||

* Anderson, G.S. (1999) Wildlife forensic entomology: determining time of death in two illegally killed black bear cubs. Journal of Forensic Sciences 44(4):856-859.<br> | |||

* Anderson, G.S. (2000) Minimum and maximum development rates of some forensically important Calliphoridae (Diptera). Journal of Forensic Sciences 45(4): 824-832.<br> | |||

* Anderson, G.S. (2001) Insect succession on carrion and its relationship to determining time of death. In Forensic Entomology: The utility of arthropods in legal investigations. Byrd, J.M. and Castner, J.L. (Eds) Boca Raton: CRC Press, p.143-175.<br> | |||

* Anderson, G.S. and Cervenka, V.J. (2002) Insects associated with the body: their use and analyses. In Advances in Forensic Taphonomy: Method, theory and archaeological perspectives. Haglund, W.D. and Sorg, M.H. (Eds) Boca Raton: CRC Press, p.174-195.<br> | |||

* Anderson, J.R. & Nilssen, A.C. (1996) Trapping oestrid parasites of reindeer: the responses of Cephenemyia trompe and Hypoderma tarandi to baited traps. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 10: 337-346.<br> | |||

* Ashworth, J.R. and Wall, R. (1994) Responses of the sheep blowflies Lucilia sericata and L.cuprina to odour and the development of semiochemical baits. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 8: 303-309.<br> | |||

* Avancini, R.M.P and Linhares, A.X. (1988) Selective attractiveness of rodent-baited traps for female blowflies. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 2: 73-76.<br> | |||

* Barton Browne, L. (1958) The choice of communal oviposition sites by the Australian sheep blowfly Lucilia cuprina. Australian Journal of Zoology p. 241-247.<br> | |||

* Barton Browne, L. (1960) The role of olfaction in the stimulation of oviposition in the blowfly, Phormia Regina. Journal of Insect Physiology 5: 16-22.<br> | |||

* Barton Browne, L. and Rogoff, W.M. (1959) The ësheep factorí and oviposition in Lucilia cuprina. Australian Journal of Science 21: 189-190.<br> | |||

* Barton Browne, L., Bartell, R.J. and Shorey, H.H. (1969) Pheremone-mediated behaviour leading to group oviposition in the blowfly Lucilia cuprina. Journal of Insect Physiology 15: 1003-1014.<br> | |||

* Benecke, M. (1998) Six forensic entomology cases: description and commentary. Journal of Forensic Sciences 43(3):797-805;1303.<br> | |||

* Benecke, M. (2001) A brief history of forensic entomology. Forensic Science International 120: 2-14.<br> | |||

* Blackith, R.E. and Blackith, R.M. (1990) Insect infestation of small corpses. Journal of Natural History 24: 699-709.<br> | |||

* Boyd, R.M. (1979) Buried buried buried body cases. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 48: 1-7.<br> | |||

* Carvalho, L.M.L. and Linhares, A.X. (2001) Seasonality of insect succession and pig carcass decomposition in a natural rainforest area in southeastern Brazil. Journal of Forensic Sciences 46(3):604-608.<br> | |||

* Catts, E.P. and Goff, M.L. (1992) Forensic entomology in criminal investigations. Annual Review of Entomology 37: 253-272.<br> | |||

* Cox, M.J (1998) Criminal concerns: a plethora of forensic archaeologist. The Archaeologist 33: 21-22.<br> | |||

* Cragg, J.B. (1956) The olfactory behaviour of Lucilia species (Diptera) under natural conditions. Annals of Applied Biology 44: 467-477.<br> | |||

* Crystall, M.M. (1983) Effect of age and ovarian development on mating in the black blowfly (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of Medical Entomology 20(2): 220-221.<br> | |||

* Dadour, I.R., Cook, D.F., Fissioli, J.N. and Bailey, W.J. (2001) Forensic entomology: application, education and research in Western Australia. Forensic Science International 120: 48-52.<br> | |||

* Davies, L. (1948) Laboratory studies on the egg of the blowfly Lucilia sericata (Mg). Journal of Experimental Biology 25: 71-77.<br> | |||

* Davies, L. and Ratcliffe, G.G. (1994) Development rates of some pre-adult stages in blowflies with reference to low temperatures. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 8: 245-254.<br> | |||

* Dougherty, M.J., Ward, R.D. and Hamilton, J.G.C. (1992) Evidence for the accessory glands as the site of production of the oviposition attractant and/or stimulant of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodiae). Chemical Ecology 18: 1165-1175.<br> | |||

* Eisemann, C.H. (1988) Upwind flight by gravid Australian sheep blowflies, Lucilia cuprina (Weidemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in response to stimuli from sheep. Bulletin of Entomological Research 78: 273-279.<br> | |||

* El Naiem, D.A. and Ward, R.D. (1990) An oviposition pheromone on the eggs of sandflies (Diptera:Psychodiae). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 84: 456-457.<br> | |||

* El Naiem, D.A. and Ward, R.D. (1991) Response of the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis to an oviposition pheromone associated with conspecific eggs. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 5:87-91.<br> | |||

* Erzinclioglu, Y.Z. (1986) An experiment with carrion flies in Hayley Wood. Nature in Cambridgeshire 28: 9-12.<br> | |||

* Fenton, A., Wall, R. and French, N.P. (1999) The effects of oviposition aggregation on the incidence of sheep blowfly strike. Veterinary Parasitology 83: 137-150.<br> | |||

* Fitzgerald, B. (1996) Research into the detection and larval infestation of buried remains by the blowfly Calliphora vicina (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera:Calliphoridae). MSc Dissertation.<br> | |||

* Gill, C.O. (1982) Microbial interaction with meats. In: Meat Microbiology. Brown, M.H. (Ed) Applied Science Publishers Ltd: London, p.225-264.<br> | |||

* Goff, M.L. (1992) Comparison of insect species associated with decomposing remains recovered inside dwellings and outdoors on the Island of Oahu, Hawaii. Journal of Forensic Sciences 36: 748-753.<br> | |||

* Grassberger, M. and Reiter, C. (2002) Effect of temperature on development of the forensically important holarctic blowfly Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Forensic Science International 128: 177-182.<br> | |||

* Green, A.A. (1951) The control of blowflies infesting slaughter-houses. I. Field observations of the habits of blowflies. Annals of Applied Biology 38: 475-494.<br> | |||

* Greenberg, B. (1990) Nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of Medical Entomology 27(5): 807-810.<br> | |||

* Greenberg, B. (1991) Flies of Forensic Indicators. Journal of Medical Entomology 28(5): 565-577.<br> | |||

* Greenberg, B. and Tantawi, T.I. (1993) Different developmental strategies in two boreal blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of Medical Entomology 30(2): 481-484.<br> | |||

* Grisbaum, G.A., Meek, C.L. and Tessmer, J.W. (1995) Effects of initial postmortem refrigeration of animal carcasses on necrophilous adult fly activity. Southwestern Entomologist 20: 165-169.<br> | |||

* Hanski, I. (1987) Carrion fly community dynamics: patchiness, seasonality and coexistence. Ecological Entomology 12: 257-266.<br> | |||

* Hall, M.J.R. (1995) Trapping the flies that cause myiasis: their responses to host-stimuli. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 89(4): 333-357.<br> | |||

* Hall, M.J.R., Farkas, R., Kelemen, F., Hosier, M.J. and El-Khoga, J.M. (1995) Orientation of agents of wound myiasis to artificial stimuli in Hungary. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 9: 77-84.<br> | |||

* Haskell, N.H., Hall, R.D., Cervenka, V.K. and Clark, M.A. (1997) On the body: Insectís life stage presence and their postmortem artefacts. In Forensic Taphonomy: The postmortem fate of human remains. Haglund, W.D. and Sorg, M.H. (Eds) Boca Raton: CRC Press, p.415-448.<br> | |||

* Holt, G.G., Adams, T.S. and Sundet, W.D. (1979) Attraction and ovipositional response of screwworms, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae), to stimulated bovine wounds. Journal of Medical Entomology 16: 248-253.<br> | |||

* Keh, B. (1985) Scope and applications of forensic entomology. Annual Review of Entomology 30: 137-154.<br> | |||

* Kuusela, S. and Hanski, I. (1982) The structure of carrion fly communities: the size and type of carrion. Holarctic Ecology 5: 337-348.<br> | |||

* Mann, R., Bass, W.M. and Meadows, L. (1990) Time since death and decomposition of the human body: variables and observations in case and experimental field studies. Journal of Forensic Sciences 35: 103-111.<br> | |||

* Norris, M.J. (1964) Laboratory experiments on gregarious behaviour in ovipositing females of the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria). Entomologia Exp Appl. 6: 279-303.<br> | |||

* Norris, K.R. (1965) The bionomics of blow flies. Annual Review of Entomology 10: 47-68.<br> | |||

* Nuorteva, P. (1977) Sarcosaprophagous insects as forensic indicators. In: Forensic Medicine: a study in trauma and environmental hazards. Volume 2: Physical Trauma. Tedeschi, C.G., Eckert, W.G. and Tedeschi, L.G. (Eds) W.B. Saunders Company: London, p.1072-1095.<br> | |||

* Payne, J.A. (1965) A summer carrion study of the baby pig Sus scrofa Linaeus. Ecology 46: 592-602.<br> | |||

* Pounder, D.J. (1991) Forensic entomo-toxicology. Journal of the Forensic Science Society 31: 469-472.<br> | |||

* Rakusin, W. (1970) Ocular interna caused by the sheep nasal bot fly (Oestrus ovis L.). South African Medical Journal 44: 1155-1157.<br> | |||

* Rodriguez, W.C. and Bass, W.M. (1985) Decomposition of buried bodies and methods that may aid in their location. Journal of Forensic Sciences 30(3): 836-852.<br> | |||

* Sharp, N. (1996) Body detection work involving the use of dogs. West Yorkshire Police, BEM, p. 8-19.<br> | |||

* Shean, B.S., Messinger, L. and Papworth, M. (1993) Observations o f differential decomposition on sun exposed v. shaded pig carrion in coastal Washigton State. Journal of Forensic Sciences 38(4): 939-949.<br> | |||

* Singh, D. and Bharti, M. (2001) Further observations on the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Forensic Science International 120: 124-126.<br> | |||

* Smith, K.G.V. (1986) A Manual of Forensic Entomology. London, Trustees of the British Museum and Cornell University Press.<br> | |||

* Smith, K.E. and Wall, R. (1997) The use of carrion as breeding sites for the blowfly Lucilia sericata and other Calliphoridae. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 11: 38-44.<br> | |||

* Sutcliffe, J.F. (1987) Distance orientation of biting flies to their hosts. Insect Science and its Application 8: 611-616.<br> | |||

* Tessmer, J.W., Meek, C.L. and Wright, V.L. (1995) Circadian patterns of oviposition by necrophilous flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Southern Louisiana. Southwestern Entomologist 24: 439-445.<br> | |||

* Turner, B.D. (1991) Forensic Entomology. Forensic Science Progress 5: 129-151.<br> | |||

* U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department <nowiki>http://www.mach.usno.navy.mil.</nowiki> Date accessed: 24th September 2002. | |||

* VanLaerhoven, S.L. and Anderson, G.S. (1999) Insect succession on buried carrion in two biogeoclimatic zones in British Columbia. Journal of Forensic Sciences 44(1):32-43.<br> | |||

* Wall, R. and Fisher, P. (2001) Visual and olfactory cue interaction in resource-location by the blowfly, Lucilia sericata. Physiological Entomology 26: 212-218.<br> | |||

* Wall, R. and Warnes, M.L. (1994) Reponses of the sheep blowfly Lucilia sericata to carrion odour and carbon dioxide. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 73: 239-246.<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Appendix A</font>== | |||

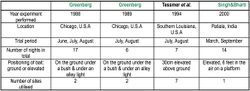

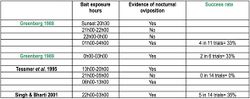

[[File:Julie spencer table 4.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 4: General information on previous nocturnal oviposition studies]] [[File:Julie spencer table 5.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 5: Times of exposure of the bait]] In conclusion, the critical times for evidence of nocturnal oviposition occur during 0h00 and 03h00.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Appendix B</font>== | |||

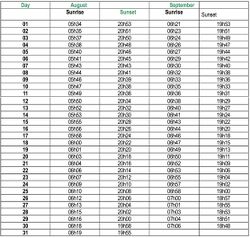

[[File:Julie spencer table 6.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 6: Sunset and sunrise times for the months of August and September]] Taken from: U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department, 24/09/02.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Appendix C</font>== | |||

[[File:Julie spencer table 7.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 7: Temperature and % relative humidity recordings, Trial 1]] [[File:Julie spencer table 8.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 8: Temperature and % relative humidity recordings, Trial 2]] [[File:Julie spencer table 9.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Table 9: Temperature and % relative humidity recordings, Trial 3]]<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==<font color=orange>Addendum (Dec 31, 2004)</font>== | |||

"I have just finished scanning the Nocturnal Oviposition article by Julie Spencer, that is posted on your site. Wanted you to know and perhaps pass along to her that much of the information she reported as having come from the study of mine that she referenced is inaccurate. She has said that my work showed that in the absence of artificial light the flies do not oviposit. That was true, but the 7 sites used ranged from complete absence of artificial light to being placed directly under extremely bright lighting. So the study shows that in the presence of various levels of artificial lighting, the flies do not oviposit." Jeanine Tessmer, Ground Spray Operations, Ouachita Parish Mosquito Abatement, 318-323-3535 <br><br> | |||

===<font color=orange>suggested readings</font>=== | |||

<i> | |||

* [[All_Mark_Benecke_Publications#Facharbeiten:_FE_for_and_from_Graduate_Students_.28School_.26_Police.29|More academic papers about Insects]]<br> | |||

* [[All_Mark_Benecke_Publications#DNA_and_DNA_Typing_-_Facharbeiten|More academic papers about DNA]]<br> | |||

* [[1997 GfE Koeln: Estimation of post mortem intervals in humans|Estimation of post mortem intervals in humans]]<br> | |||

* [[Goff Benecke A Fly for the Prosecution|"A Fly for the Prosecution by Lee Goff"]]<br> | |||

* [[Forensic Entomology Distinction of bloodstains from fly artifacts|Distinction of bloodstain patterns from fly artifacts]]<br> | |||

* [[2008 Acta biologica Benrodis: A brief survey of the history of forensic entomology|A brief survey of the history of forensic entomology]]<br> | |||

* [[2011 Studien zur Koelner Kirchengeschichte: Kaeferfunde und andere biologische Spuren im Schrein des Hl Severin|Käferfunde und weitere biologische Spuren aus dem Holzschrein des hl. Severin]] <font size="-2" color="#FF0000" face="helvetica">GERMAN TEXT</font><br> | |||

* [[2014 08 International Congress of Dipterology|Arthropods on mummies in the Catacombe dei Cappuccini in Palermo, Italy]]<br> | |||

</i> | |||

{{Addressfooter}} | {{Addressfooter}} | ||

__NOTOC__ | |||

__NOEDITSECTION__ | __NOEDITSECTION__ | ||

Latest revision as of 21:22, 7 July 2017

Name: Julie Spencer

Dissertation submitted as part of the requirement for MSc/PGDip Forensic Archaeology

Title: The nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies in the southwest of Britain during the months of August and September

Bournemouth University, School of Conservation Sciences, 2003

The nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies in the southwest of Britain

during the months of August and September

[More articles from MB] [Articles about MB]

Abstract

Blowflies are ubiquitous insects and have an ability to disperse, are small in size and have short generation times, therefore, it is hardly surprising that corpses are readily found colonised by insects and that as a corpse ages and the decomposition processes proceed, a different fauna will invade the body. With a change in attractiveness of the corpse through time, a succession of insect species will be encountered. These species will give some indication as to the history of the corpse, how old it is and what has happened to it. The postmortem interval (PMI) is one of the most important aspects of forensic entomology, since it aids in establishing a correct time frame in which the crime will have taken place. However, various factors may alter PMI, namely the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies, seeing as it can alter PMI by as much as 12 hours.

Determination of the exact time of oviposition by blowflies had generally been made in the light of the conventional belief that blowflies are neither active nor do they lay eggs during the night. This method of estimating the time of oviposition was modified when Greenberg (1990:807) and Singh & Bharti (2001:124) both reported nocturnal oviposition by calliphorid species that are occasionally used as forensic indicators. The present research was concerned with investigating whether blowflies were active at night and laid their eggs during the months of August and September in South West Britain. It was found that nocturnal oviposition did not occur in any of the nine night trials undertaken.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Background to project

Forensic entomology is a discipline that has increased in importance over the past few decades. Today, the principal role of forensic entomology is to provide biological inferences regarding the circumstances surrounding, and the length of time, since human death, based upon examination of arthropods collected from or near corpses (Keh 1985:137; Catts & Goff 1992:253; Haskell et al. 1997:416; Benecke 2001:2). As early as 1979, Boyd recognised that entomologists could give a minimum time span on the time of death, i.e. the postmortem interval (PMI). In a death investigation, the time of death will focus the investigation into a correct time frame. Insects are attracted by specific states of decay, and particular species colonise a corpse for limited periods of time (Benecke 1998:799; Anderson 1999:856).

Consequently, there are two fundamental ways insects are used to estimate time of death. Firstly, blow fly developmental rates are used when the body is relatively fresh, i.e. in the first few hours, days or weeks after death. Secondly, faunal succession is analysed since different species of insects infest the body at different times (Boyd 1979:4; Haskell et al. 1997:416; Benecke 1998:798; Anderson & Cervenka 2002:174). Sarcosaprophagous flies, i.e. those which feed on dead animal material, particularly calliphorids, are recognised as the first wave of the faunal succession on human cadavers (Nuorteva 1977:1080; Smith 1986). They are, therefore, the primary and most accurate forensic indicators of time since death (Grassberger & Reiter 2002:177).

In general, the blowflies are the first insects to colonise remains, although the species will vary with geographical region and season (VanLaerhoven & Anderson 1999:32; Carvalho & Linhares 2001:604). They are constantly in search of fresh carrion to lay their eggs on and this explains their early presence on corpses. Eggs are usually laid in large batches, up to 250 eggs at a time. Blowflies will lay their eggs in almost any orifice and it has been estimated that as many as 40,000 eggs may be laid on any adult body (Greenberg 1991:566; Sharp 1996:9). If one female has laid her eggs, many others become attracted to the same area and lay their eggs at the same site, therefore, the egg mass may be several square centimetres in size (Barton Browne et al. 1969:1003; Anderson 2001:144; Anderson & Cervenka 2002:174). Oviposition in blowflies is elicited primarily by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds as well as moisture, pheromones and tactile stimuli (Ashworth & Wall 1994:303).

Blowflies are diurnal species and are considered to be inactive at night. Therefore, eggs are generally not laid at night, and a body deposited at night may not attract flies until the following day (Anderson 1999:856; Anderson 2001:145). At present, the research into the nocturnal oviposition behaviour of blowflies has been limited. Greenberg (1990:807) and Singh and Bharti (2001:124) maintain that calliphorid flies can lay eggs during the night. However, research carried out by Tessmer et al. (1995:439) concluded that egg deposition does not occur in the nocturnal hours.

In a given situation a forensic archaeologist has the capacity to provide guidance and advice on other fields of expertise by having a basic understanding of a broad range of forensic sciences from pathology and forensic anthropology, to forensic entomology and environmental archaeology. For example, a forensic archaeologist may be asked to collect samples in the absence of an entomologist. Therefore, it is imperative that a forensic archaeologist keeps up to speed on the progress being made in various fields, especially the up and coming field of forensic entomology. By understanding the following study, forensic archaeologists will allow themselves to become more judgemental with regards to estimates in postmortem interval (PMI) and this is, without doubt, one of the most fundamental elements in a forensic investigation.

Factors influencing the oviposition of blowflies

Blowflies are ubiquitous insects that impact on man and animals in many ways. There are positive and negative aspects associated with these invertebrates. They transmit a variety of human diseases and can cause economic loss due to myiasis or fly strike. For the most part they are considered highly detrimental. Nonetheless, they can also be regarded as beneficial insects. For example in maggot therapy and as pollinators of agricultural crops in controlled areas. However, knowledge of blowflies can also be employed in a unique setting. Their ability to rapidly locate a body enables them to colonise human and animal remains that have been wrapped, buried or otherwise protected. The omnipresent nature of insects makes their eventual appearance at a death scene a near certainty. In consequence, their life cycles and developmental rates can aid in determining the time of death in criminal cases (Nuorteva 1977:1072; Avancini & Linhares 1988:73; Turner 1991:132; Anderson 2000:824).

Cadavers undergo a series of predictable changes during decomposition, and are ëvisitedí by a succession of flies and other insects (Goff 1992:748). This ordered process has handed us an invaluable tool for estimating the age of cadavers, and the biology of this process has resulted in the science of forensic entomology (Dadour et al. 2001:48). Fly developmental rates underpin the accuracy of the PMI.

Calliphora vicina (Robineau-Desvoidy), commonly known as the blue bottle, is the most frequent species of blowfly found on human corpses in the UK (Smith 1986; Pounder 1991:469). Adult C. vicina are large and conspicuous due to their slow, powerful buzzing flight.

They are extremely abundant in open and urban surroundings as well as in association with humans and their environments. The species has an almost global distribution, being found throughout the Holarctic region as well as South America, North India, Australia and New Zealand (Smith 1986). In the climatic context of northern Europe, certain species, particularly Calliphora vicina, are of special forensic interest because of their ability to develop to pre-adult stages at 3-4ƒC, and the fact that adult populations occur over very long seasonal spans including cool months. They exist in most habitats from sea level to high ground, and both urban and rural habitats (Davies & Ratcliffe 1994:245).

Blowflies, such as Calliphora, owe their forensic importance to their ability to locate human remains within seconds of death and to oviposit within an hour in favourable conditions (Pounder 1991:469; VanLaerhoven & Anderson 1996; Haskell et al. 1997). Nuorteva (1977:1080) maintains that an intact dead body does not immediately attract sacrosaprophagous flies for oviposition. In the presence of vomitus, blood or an open wound, however, oviposition may be established in a few minutes. In fact, open wounds may induce oviposition in the still-living body. Oviposition of blowflies on woundless corpses starts in general the second day after death, but it may also occur earlier when flies are abundant in the environment and the dead body is lying in sunshine (Nuorteva 1977:1081).

There are numerous species of sarcosaprophagous flies that are confined to environments of a quite specific type (e.g. forests, shores, hill tops, cities), and these flies may by their eggs verify the transport of a corpse through their domain. Only a few species, however, possess eggs characteristic enough to be identified directly. In considering forensic evidence based on fly eggs, it is necessary to remember that fly eggs are easily destroyed by unfavourable environmental conditions, especially by heat and dessication (Davies 1948:71; Nuorteva 1977:1080).

The oviposition behaviour of insects is usually complex (Barton Browne 1960:16). The attraction of blowflies to their hosts involves a broad range of behaviours including initial activation, orientation and landing behaviour culminating in oviposition. Each stage requires a combination of visual and olfactory cues with tactile cues possibly acting in the final stages (Ashworth & Wall 1994:303). Oviposition in sandflies is also controlled through a combination of complex interactions between environmental, physical and chemical factors (Nieves et al. 1997:733). Oviposition is elicited primarily by the presence of ammonia-rich compounds, as well as moisture, pheromones and tactile stimuli (Ashworth & Wall 1994:304). However, some species of blowfly are dependent on their gonadotrophic development stage in order to be attracted to carrion baits (Crystall 1983:220).